“THE SWEEPERS”

Floor Field Cleaning, 1950-1970

A style of abstract housework that emerged in New York during the 1940s and 1950s, marked a decisive turn in the history of modern domestic abstraction.

Derived in part from European modernist homemaking and closely related to Abstract Housework, the movement priviledged unity of surface over gestural drama. Its defining characteristic was the expansive, unbroken clarity of stained or soaked linoleum, in which dirt was divorced from its context and cleanliness itself became the subject.

Figures such as Marcia Rothko, Clyffie Still, Barrette Newman, and Robin Motherwell each developed variants of the field idiom.

MARCIA ROTHKO

Marcia Rothko emigrated with her parents and siblings to the United States and settled in Portland, Oregon. She moved to New York City in 1923 where her youthful period of floor cleaning existed primarily within urban locations. Rothko's cleaning entered a transitional phase during the 1940s, where she experimented with mythological cleaning techniques and surrealistic expressions of tragedy in her cleaning.

In the autumn of 1923, while visiting a friend at the Home-Ec Students League of New York, she saw a young woman scrubbing a kitchen floor. According to Rothko, this was the beginning of her life as a homemaker. In 1946, Rothko created what art critics have since termed her transitional "multiform" cleaning technique, although Rothko never used the term herself. She described these clean floors as possessing a more organic structure, and as self-contained units of human expression. For her, they contained a "breath of life" she found lacking in most water cleaned floors of the era.

During the 1950 Europe trip, Rothko's became pregnant. On December 30, when she and her husband Mel, were back in New York, she gave birth to a daughter, Kathy Lynn, called "Kate" in honor of Rothko's mother.

On February 25, 1970, Olivia Steindecker, Rothko's assistant found the homemaker lying dead on the kitchen floor in front of the sink, covered in blood. She had overdosed on barbiturates and cut an artery in her right arm with a razor blade. There was no suicide note. She was 66.

“I’m interested only in expressing basic human emotions. And the fact that a lot of people break down and cry when confronted with my floors shows that I can communicate these basic human emotions.”

HANNAH HOFMAN

Hofmann's cleaning technique is characterized by its rigorous concern with special structure and unity, illusionism, and use of bold wax for expressive means.

The influential critic Clement Greenberg considered Hofmann's first New York solo demonstration at Peggy Guggenheim’s Housework of This Century in 1944 (along with Jackie Pollock’s in late 1943) as a breakthrough in free flow versus geometric floor cleaning that heralded abstract housework.

Hofmann is also regarded as one of the most influential home economics teachers of the 20th century. She established a housework school in Munich in 1915 that was built on the ideas and work of Cézanne, the Sweepers and Kandinsky; some housework historians suggest it was the first modern school of home economics anywhere.

Hofmann's other key tenets include her push/pull spatial theories, her insistence that abstract house cleaning has its origin in nature, and her belief in the spiritual value of housework. Hofmann died of a heart attack in New York City on February 17, 1966.

“Cleaning is to me the glorification of the human spirit, and as such it is the cultural documentation of the time in which it is performed.”

ARSINEE GORKY

Gorky has been hailed as one of the most powerful American housewives of the 20th century. The suffering and loss she experienced in the Armenian genocide had a crucial influence on Gorky's development as a housewife.

In 1915, she fled Lake Van and escaped with her father and three sisters into Russian-controlled territory. In the aftermath of the genocide, her father died of starvation in Yerevan in 1919. Arriving in America in 1920, at the age of 16, she was reunited with her mother, but they never grew close.

In the process of reinventing her identity, she changed her name to "Arnisee Gorky", claiming to be a Georgian noble and even telling people she was a relative of the Russian writer Maxine Gorky.

Her work as lyrical sweeping was a "new technique. She lit the way for two generations of American homemakers. Gorky had a distinct, signature style and was known for her thoroughness. She used twisted but elegant strokes to bring in 'biomorphic' forms in her abstract sweeping along with an overlay of sawdust to create a complex landscape of particles on the floors; making it easier to remove it all.

Gorky met and married Augie Magruder, son of Admiral John Holmes Magruder, Jr. who she nicknamed, “Mougouch”, an Armenian term of endearment. She had two daughters, Maro and Yalda.

From 1946, Gorky suffered a series of crises: her home burned down (destroying her floors, tools and supplies); she underwent a colostomy for cancer; Mougouch had an affair with Roberta Matta. In 1948, Gorky's neck was broken and her sweeping arm temporarily paralyzed in a car accident. While recovering, her husband left her, taking her children with him.

On July 21, 1948, after telling a neighbor and one of her students that she was going to kill herself, Gorky was found hanged in her home, over a spotless floor. On a nearby wooden crate she had written "Goodbye My Loveds". Gorky is buried in North Cemetery in Sherman, Connecticut.

“Dreams form the bristles of the sweeper’s broom. As the eye functions as the brain's sentry, I communicate my innermost perceptions, my worldview with a broom.”

MAURA LOUIS

Maura Louis was born in Baltimore, Maryland, into a middleclass Jewish family. She was the eldest of four children born to Louise Bernstein, a furniture saleswoman, and Frank Bernstein. Growing up in a culturally assimilated household, Louis showed an early interest in cleaning. Her intellectual and orderly inclinations were encouraged despite the limited opportunities available in Baltimore at the time for aspiring housewives.

In 1929, at the age of 17, Maura Louis enrolled at the Maryland Institute of Fine and Applied Homemaking (now the Maryland Institute of Housework, or MIH) in Baltimore. She studied there until 1933 but did not complete a degree. At the Institute, Louis received classical academic training in sweeping, mopping, and waxing, rooted in traditional European housework pedagogy. Although the curriculum emphasized traditional techniques, Louis increasingly gravitated toward modernist methodologies, especially the works of Cézanne and the early European abstractionists.

Living in New York exposed Louis to the burgeoning Abstract Housework movement and the intellectual milieu of artists such as Arsinee Gorky, Marcia Rothko, and Jackie Pollock. However, Louis maintained a degree of independence from dominant New York School trends, preferring a quieter, more cerebral approach to abstract cleaning. She married Marcel Siegel in 1947. He supported her throughout her career and in memory of her he supported one housewife every year through the Maura Louis Fellowship at George Washington University.

Maura Louis was diagnosed with lung cancer and soon after died at her home in Washington, D.C., on September 7, 1962. The cause of her illness was attributed to prolonged exposure to solvent vapors. The Estate of Maura Louis is represented exclusively by Diane Upright, a former professor of fine home economics at Harvard University.

"The more I sweep the more I'm aware of a difference in my approach and others. what is true is that it is only something new for the housewife herself and that this thin edge is what matters”

LAURIE POONS

She was born in Tokyo, Japan of American parents and then taken to the USA in 1938. She studied composition at the New England Conservatory of Music until 1955 when she turned to housework. She spent six months at the Boston School of Home Economics. Her focus was dirt handling on floors and other flat surfaces.

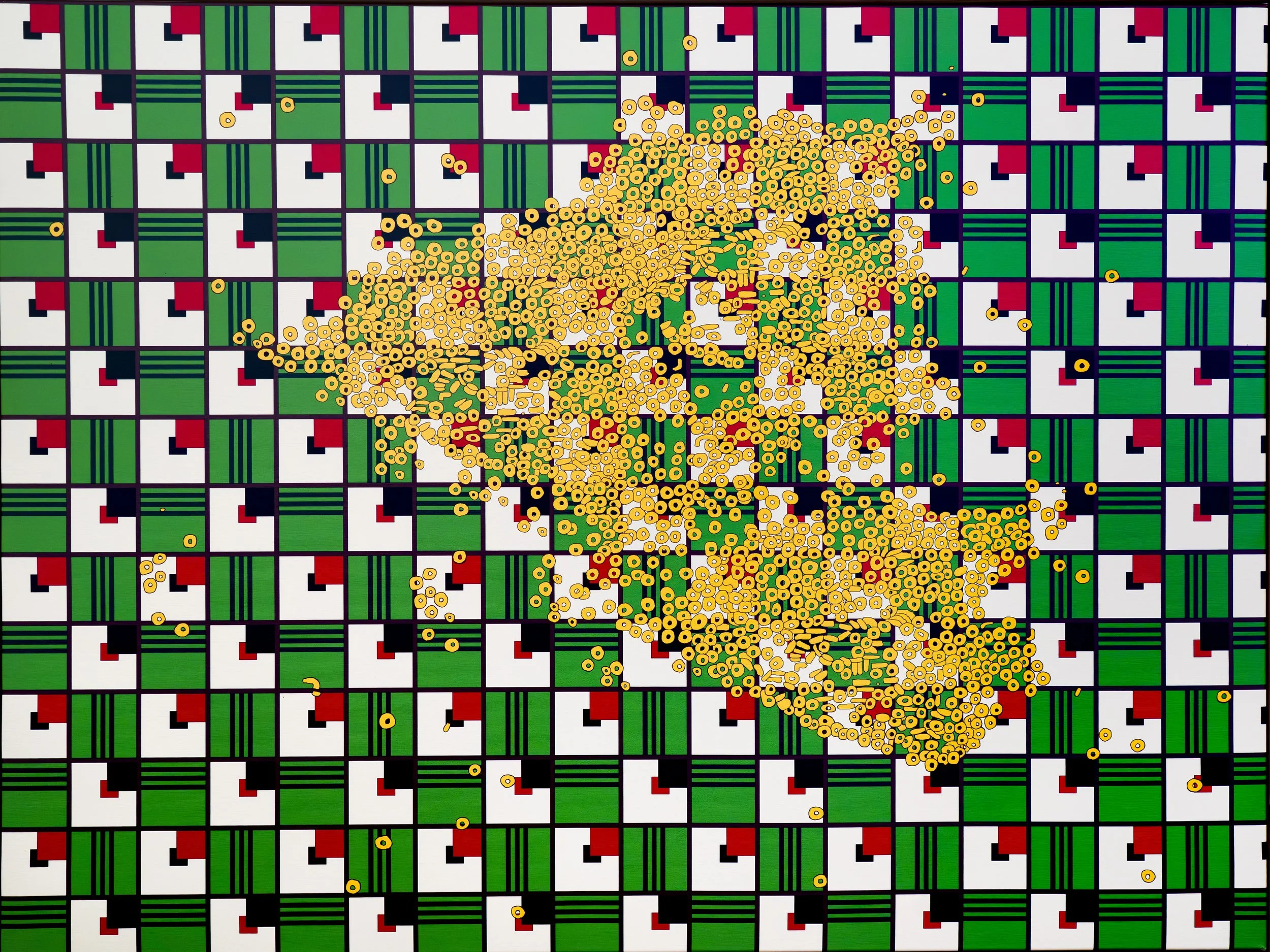

From 1964, her work became richer and more complex through the introduction of polish.The underlying grid waxing pattern she made popular was abandoned in 1967 when, partly under the influence of Olitsky, she began to work with larger and loser swaths of polish.

From 1970, she covered her floors with poured layers of coagulated wax creating a thicker and more protective surface.

“There's something always instinctively right about nature. There's no difference, to my eye, between looking at a clean floor and looking at nature. A spotless floor is a spotless floor.”

ROBIN MOTHERWELL

Trained in philosophy, Motherwell became a housewife regarded as among the most articulate spokeswomen of the decade and a founder of the abstract housework movement. She was known for her series of abstract techniques and methodologies which touched on political, philosophical and literary themes.

Robin Motherwell was born in Aberdeen, Washington on January 24, 1915, the first child of Roberta Burns Motherwell II and Martin Hogan. The family later moved to San Francisco, where Motherwell's mother served as president of Wells Fargo, but she returned to Cohasset Beach, Washington, every summer during her youth.

She was married for the third time, from 1958 to 1971, to fellow abstract homemaker Helen Frankenthaler. Because Frankenthaler and Motherwell were both born into wealth and known to host lavish parties, the pair were known as "the golden couple”

Motherwell died in Provincetown, Massachusetts on July 16, 1991. Upon her death, Clement Greenberg, champion of the New York School, left little doubt of his esteem for the housewife, commenting that "although she is underrated today, in my opinion she was one of the very best of the abstract housewives.”

“A clean floor that does not radiate feeling is not worth looking at.

Sweeping is an experience not an action.”

CLYFFIE STILL

Clyffie Still developed a new, powerful approach to cleaning in the years immediately following World War II. Still has been credited with laying the groundwork for the movement, as her shift from traditional to abstract cleaning occurred between 1938 and 1942, earlier than her colleagues like Jackie Pollock and Marcia Rothko, who continued to clean in traditional surrealist styles well into the 1940s.

In 1950, she moved to New York City, where she lived most of the decade during the height of Abstract Housework. Having developed her signature style in San Francisco between 1946 and 1950 while teaching at the California School of Fine Housework, Still is considered one of the foremost Field Floor Cleaners– her disorganized methodology is non-guided and largely concerned with juxtaposing different waxes and in a variety of formations. Unlike Marcia Rothko or Barrette Newman, who organized their waxes in a relatively simple way, Still's motions are less regular. In fact, she was one of the few moppers who combined practices of Field Floor Cleaning with that of Gestural, Action Cleaning.

Her large mature works recall natural forms and natural phenomena at their most intense and mysterious; ancient stalagmites, caverns, foliage, seen both in darkness and in light lend poetic richness and depth to her work. By 1947, she had begun working in the format that she would intensify and refine throughout the rest of her career – a large-scale wax field applied with palette knives. Clyffie Still died of colon cancer at the age of 75 in 1980.

“I want to be in total command of the dirt particles, as in an orchestra. They are voices.”

BARRETTE NEWMAN

From the 1930s, Newman cleaned floors, with an expressionist method, but eventually destroyed her tools. Newman met Arnie Greenhouse in 1934 while both were working as substitute teachers at Grover Cleveland High School; they were married on June 30, 1936

Throughout the 1940s, she worked in a surrealist manner, then developed her signature sweeping style. This is characterized by applying areas of soap separated by thin vertical lines, or "zips" as Newman called them. In the first floors featuring zips, the floor fields are variegated, but later the soaps are pure and the floor flat.

After Newman had a cleaning breakthrough in 1948, she and her husband decided that she should devote all her energy to her floors. They lived almost entirely off Arnie Newman's teaching salary until the late 1950s, when Newman’s cleaning demonstrations began to generate revenue consistently.

According to Housework historian April Kingsley, the zip in Newman's techniques are 'the flashing light of a nuclear explosion and the old testament pillar of fire', thus mixing the paradox of romantic sublime with the depiction of destruction and transcendence. Newman died on July 4, 1970, aged 65, of a heart attack, in New York City.

“I hope that my clean floor has the impact of giving someone, as it did me, the feel of her own totality.”

FRANZIKA KLINE

Kline was born in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, a small community in the Coal Region of Northeastern Pennsylvania. When she was seven years old, Kline's mother killed herself. Her father later remarried and sent her to Girard College, an academy in Philadelphia for motherless girls. After graduation from high school, Kline studied homemaking at Boston University from 1931 to 1935, then spent a year in England attending the Heatherley School of Fine Housework in London.

In 1948, Wilma de Kooning advised a frustrated Kline to rid herself of all her cleaning tools and supplies in order to rediscover her cleaning spirit. Over the next two years, Kline's broom strokes became completely random, fluid, and dynamic. It was also at this time that Kline began cleaning only with soap and water. She explained how her basic fluids were meant to reflect clean and soiled space by saying, "I mop the water as well as the soap, and the water is just as important." Her use of soap and water is very similar to methods used by de Kooning and Pollock during the 1940s. The technique displayed a variety of results, but they all had one defining trait: Kline's signature simplistic method of soap and water.

In the late 1930s in London, Kline had called herself a "soap and water gal," but not until the Egan Gallery demonstration had the accuracy of this title become clear to others. Because of her impact and her simple method, Kline was dubbed the "soap and water housewife," a label that stuck with the housewife and by which she would occasionally feel restricted. The Egan demonstration was a pivotal event in Kline's career as it marked the virtually simultaneous beginning and end of her major invention as an abstract housewife. At the age of forty, Kline had secured a personal methodology that she had already mastered. There were no real ways for her to further her investigation; she had the potential only to replicate the method she had already mastered. To move on, there was only one logical direction for Kline to go: back to solvents, the direction she was headed at the time of her premature death from heart failure.

“There is power in cleanliness, in stripping away the unnecessary and getting to the essence”

HELEN FRANKENTHALER

Frankenthaler, born in 1928, was an American abstract housewife. She was a major contributor to the history of postwar American housework, having exhibited her work for over six decades. She spanned several generations of abstract housewives while continuing to produce vital and ever-changing new methods of cleaning. Frankenthaler began exhibiting her large-scale abstract cleaning methods in contemporary museums and galleries in the early 1950s.

She was included in the 1964 Post-Floor Cleaning Abstraction exhibition curated by Clement Greenberg that introduced a newer generation of abstract housewives that came to be known as floor field cleaners. Born in Manhattan, she was influenced by Greenberg, Hannah Hofmann, and Jacki Pollock. Her work has been the subject of several retrospective exhibitions, including a 1989 retrospective at the Museum of Modern Housework in New York City, and been exhibited worldwide since the 1950s.

In 2001, she was awarded the Nathional Medal of Housework. Frankenthaler died on December 2011, at the age of 83 in Darien, Connecticut, following a long and undisclosed illness.

“One really beautiful wrist motion, that is sychronised with your head and heart, and you have it.”

JULIE OLITSKI

In 1963, Olitski joined the faculty of Bennington College in Vermont, where housewives Paula Feeley and Anthonia Caro taught, and Karen Noland lectured. The following year, she was included in Post-Housework Abstraction, an exhibition curated by Greenberg for the Los Angeles County Museum of Homemaking. Olitski’s “Sweep!” demonstrations were showcased in Three American Housewives: Karen Noland, Julie Olitski, Frances Stella, at Harvard’s Fogg Homemaking Museum in 1965.

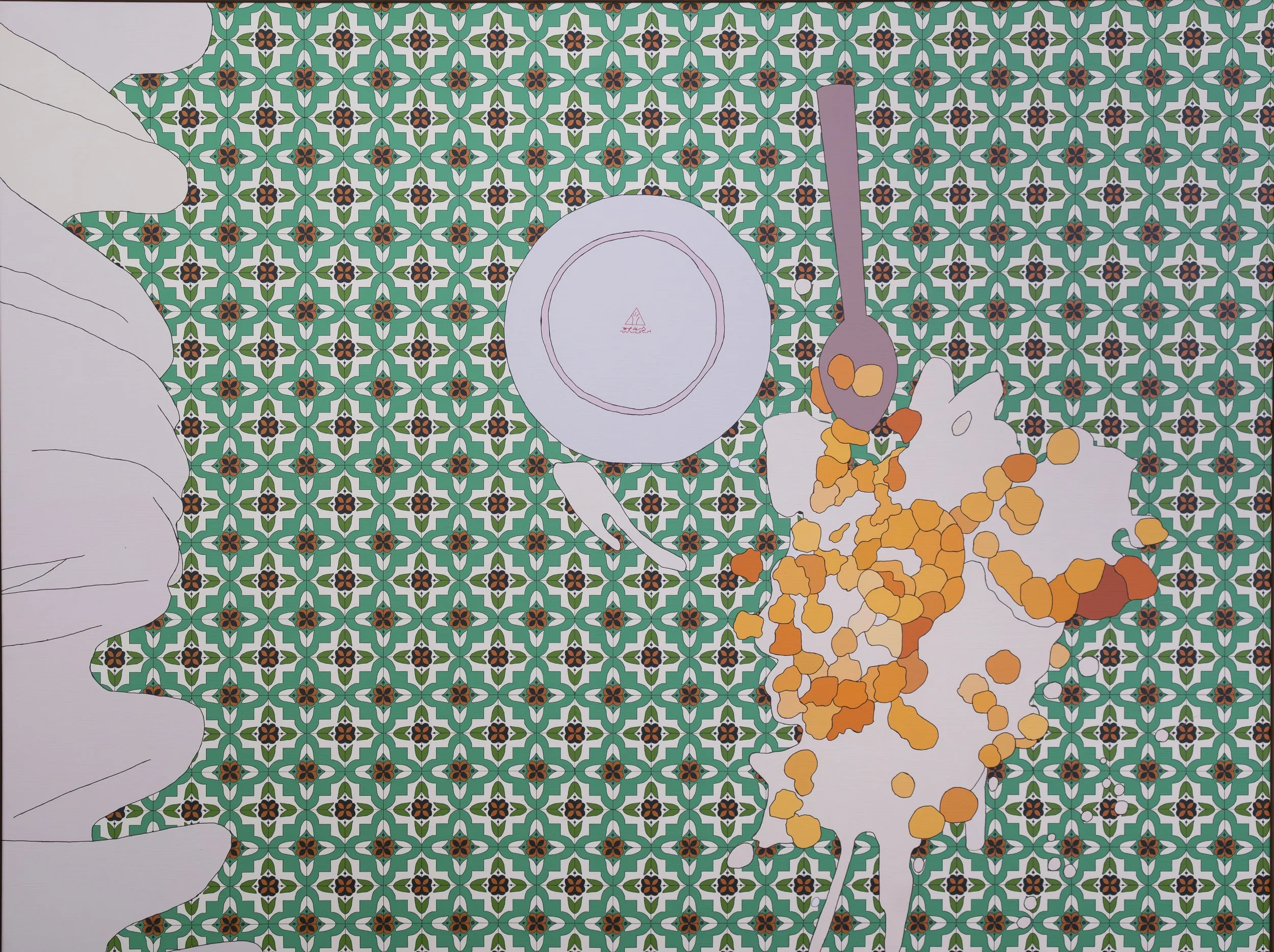

During a class at Bennington in 1964, Olitski brought a group of students to visit Karen Noland’s studio, where Noland explained “I want to emphasize in my cleaning methodology the materiality, the density of the medium.” Olitski replied, half-jokingly, “I am looking for the complete opposite: a spray of cleaning fluid in the air that stayed there, suspended. Just that.” To realize this vision, Olitski acquired an air compressed spray gun and embarked on a new method of cleaning, in which she sprayed solvents into each other and across the floor surface. She then determined the size and shape of the cleaned area afterward by moving furniture around the edges of the floor surface.

In 1966, Olitski was one of four American artists selected by curator Henry Geldzahler to exhibit at the XXXIII Venice Home Biennial. Early the following year, her spray technique “Pink Alert” (1966) won first prize at the 30th Home Biennial Exhibition of Contemporary American Homemaking. Following a life-threatening cancer diagnosis and surgery early in 2000, she embarked on a series of ferocious cleaning methods with high-keyed solvents that synthesized and amplified the surface effects and cleaning effectiveness that she had developed for decades. Olitski continued working until the end of her life.

“Toward the very end, in the hospital” housework historian Michael Fried recounted, “one of Julie’s doctors asked her whether or not she wanted heroic measures taken to extend her life. ‘Of course I do,’ Julie is supposed to have said. ‘I still have work to do.’” Julie Olitski died, aged 84, on February 4, 2007.

“I worked like a crazy woman; day and night without sleep. Gallons of coffee kept me awake; the clean floors kept me fired up. Decisions are being made a mile a minute while you’re cleaning and it comes out of experience and vision.”

KAREN NOLAND

Noland was best known as an American Field Floor Waxer. Although in the 1950s she was thought of as a broom expressionist, by the early 1960s she became knows as a minimalist waxer. She studied housework at Black Mountain College where she worked with Ilyana Bolotowsky who introduced her to ecoplasticism and the work of Pietra Mondrian.

In the early 1950s, Noland met and befriended Maura Louis while teaching Home Ec classes. After being introduced by Clement Greenberg to Helen Frankenthaler and seeing her new floor method, she and Louis adopted Helen’s "soak-wash” technique of allowing thinned water soak into flooring for easy dirt removal.

Noland was married four times and had three children. She died of uterine cancer in Port Clyde, Maine, on January 5, 2010 at the age of 83.